ТОР 5 статей:

Методические подходы к анализу финансового состояния предприятия

Проблема периодизации русской литературы ХХ века. Краткая характеристика второй половины ХХ века

Характеристика шлифовальных кругов и ее маркировка

Служебные части речи. Предлог. Союз. Частицы

КАТЕГОРИИ:

- Археология

- Архитектура

- Астрономия

- Аудит

- Биология

- Ботаника

- Бухгалтерский учёт

- Войное дело

- Генетика

- География

- Геология

- Дизайн

- Искусство

- История

- Кино

- Кулинария

- Культура

- Литература

- Математика

- Медицина

- Металлургия

- Мифология

- Музыка

- Психология

- Религия

- Спорт

- Строительство

- Техника

- Транспорт

- Туризм

- Усадьба

- Физика

- Фотография

- Химия

- Экология

- Электричество

- Электроника

- Энергетика

14 страница. It would be difficult to find a more happy and contented people than the primitives in the Torres Strait Islands as they lived without contact with modern

It would be difficult to find a more happy and contented people than the primitives in the Torres Strait Islands as they lived without contact with modern civilization. Indeed, they seem to resent very acutely the modern intrusion. They not only have nearly perfect bodies, but an associated personality and character of a high degree of excellence. One is continually impressed with happiness, peace and health while in their congenial presence.

These people are not lazy, but they do not struggle over hard to obtain food. Necessities that are not readily at hand they do not have. Their home life reaches a very high ideal and among them there is practically no crime.

In their native state they have exceedingly little disease. Dr. J. R. Nimmo, the government physician in charge of the supervision of this group, told me in his thirteen years with them he had not seen a single case of malignancy, and had seen only one that he had suspected might be malignancy among the entire four thousand native population. He stated that during this same period he had operated several dozen malignancies for the white population, which numbers about three hundred. He reported that among the primitive stock other affections requiring surgical interference were rare.

The environment of the Torres Strait Islanders provides a very liberal supply of sea foods and fertile islands on which an adequate quantity of tropical plants are readily grown. Taro, bananas, papaya, and plums are all grown abundantly. The sea foods include large and small fish in great abundance, dugong, and a great variety of shellfish. These foods have developed for them remarkable physiques with practically complete immunity to dental caries. Wherever they have adopted the white man's foods, however, they suffer the typical expressions of degeneration, such as, loss of immunity to dental caries; and in the succeeding generations there is a marked change in facial and dental arch form with marked lowering of resistance to disease.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 12

ISOLATED AND MODERNIZED NEW ZEALAND MAORI

BECAUSE of the fine reputation of the racial stock in its primitive condition, it was with particular interest that studies were made in New Zealand. Pickerill (1) has made a very extensive study of the New Zealand Maori, both by examination of the skulls and by examination of the relatively primitive living Maori. He states:

In an examination of 250 Maori skulls--all from an uncivilized age--I found carious teeth present in only two skulls or 0.76 per cent. By taking the average of Mummery's and my own investigations, the incidence of caries in the Maori is found to be 1.2 per cent in a total of 326 skulls. This is lower even than the Esquimaux, and shows the Maori to have been the most immune race to caries, for which statistics are available.

Comparing these figures with those applicable to the present time, we find that the descendants of the Britons and Anglo-Saxons are afflicted with dental caries to the extent of 86 per cent to 98 per cent; and after examining fifty Maori school children living under European conditions entirely, I found that 95 per cent of them had decayed teeth.

It will be noted that the basis of computation in the above is percentage of individuals with caries. I am using in addition to these figures the percentage of teeth attacked by dental caries. Expressed in percentage of teeth affected the figure for Pickerill's group would be 0.05 or 1 in 2,000 teeth.

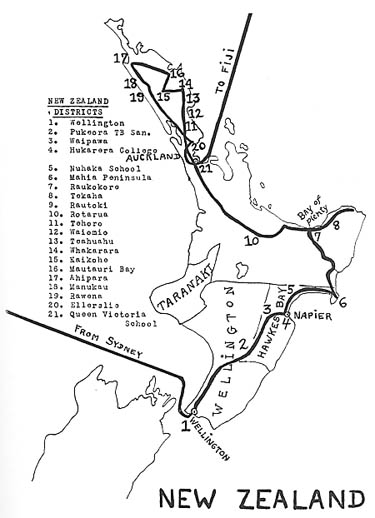

We were deeply indebted to the government officials in New Zealand for their invaluable assistance. In anticipation of making these studies I had been in correspondence with the officials for over two years. When we arrived at Auckland, New Zealand, on our way to Australia, our ship was in port for one day. We were met by Colonel Saunders, Director of Oral Hygiene in the New Zealand Department of Public Health who had been sent from the capitol at Wellington to offer assistance. A personal representative of the Government was sent as guide, and transportation to the various Maori settlements in which we wished to make our studies was provided.

|

New Zealand is setting a standard for the world in the care of growing children as well as in many other health problems. A large percentage of the schools in New Zealand are provided with dental service. A specially trained woman was in charge of the work in each school under Colonel Saunders' supervision. The operations performed by these young women on children far exceeded in quality the average that I have seen by dentists in America. Their plan gives dental care to children twelve years of age and under, provided the parents express a wish that their children receive that care. The service was being extended rapidly to all communities. Since my return, I have learned that the work is being organized to provide for every community of New Zealand. The art of the Maori gives evidence of their great ability and skill in sculpturing. Boys and girls do beautiful carving and weaving. All native buildings and structures are embellished with carvings often in fine detail.

It was most gratifying to find neat and well-appointed dental office buildings for both natives and whites, located beside a large number of the public schools throughout New Zealand. In many communities two or three schools were served by the same operator. Children were either brought to the central dental infirmary or provision was made for an operating room in the vicinity of each school. The operator went from district to district. A typical dental infirmary is shown in Fig. 68, with Colonel Saunders and one of his efficient women operators in the foreground. I had suggested that I should be glad to have observers from the Department of Health accompany us or arrange to be present at convenient places to observe the conditions and to note my interpretations of them. From two to five such observers were generally present, including the official representative of the department. The planning of the itinerary was very greatly assisted by a Maori member of Parliament, Mr. Aparana Ngata.

|

| FIG. 68. The New Zealand government provides nearly universal free dental service for the children, regardless of color, to the age of twelve years. This is a typical dental clinic maintained in connection with the school system. They are operated by trained dental hygienists. The director of the system, Colonel Saunders, is seen in the picture. |

Although New Zealand is a new country with a relatively small population, there being approximately only a million and a half individuals, the building of highways has rapidly been extended to include all modernized sections. In order to reach the most remote groups it was often necessary to go beyond the zone of public improvements and follow quite primitive trails. Fortunately this was possible because it was the dry season. Even then many streams had to be forded, which would have been quite impossible at other seasons of the year. We were able to average approximately a hundred miles of travel per day for eighteen days, visiting twenty-five districts and making examinations of native Maori families and children in native schools, representing various stages of modernization. This included a few white schools and tubercular sanitariums.

Since over 95 per cent of the New Zealanders are to be found in the North Island, our investigations were limited to this island. Our itinerary started at Wellington at the south end of the North Island and progressed northward in such a way as to reach both the principal centers of native population who were modernized and those who were more isolated. This latter group, however, was a small part of the total native population. Detailed examinations including measurements and photographic records were made in twenty-two groups consisting chiefly of the older children in public schools. In the examination of 535 individuals in these twenty-two school districts their 15,332 teeth revealed that 3,420 had been attacked by dental caries or 22.3 per cent. In the most modernized groups 31 to 50 per cent had dental caries. In the most isolated group only 2 per cent of the teeth had been attacked by dental caries. The incidence of deformity of dental arches in the modernized groups ranged from 40 to 100 per cent. In many districts members of the older generations revealed 100 per cent normally formed dental arches. The children of these individuals, however, showed a much higher percentage of deformed dental arches.

These data are in striking contrast with the condition of the teeth and dental arches of the skulls of the Maori before contact with the white man and the reports of examinations by early scientists who made contact with the primitive Maori before he was modernized. These reports revealed only one tooth in 2000 teeth attacked by dental caries with practically 100 per cent normally formed dental arches.

My investigations were made in the following places in the North Island. The Pukerora Tubercular Sanatorium provided forty native Maori for studies. These were largely young men and women and being in a modern institution they were receiving the modern foods of the whites of New Zealand. Their modernization was demonstrated not only by the high incidence of dental caries but also by the fact that 90 per cent of the adults and 100 per cent of the children had abnormalities of the dental arches.

The Hukarera College for Maori girls is at Napier. These girls were largely from modernized native homes and were now living in a modern institution. Their modernization was expressed in the high percentage of dental caries and their deformed dental arches.

At the Nuhaka school an opportunity was provided through the assistance of the government officials to study the parents of many of the children. Tooth decay was wide-spread among the women and active among both the men and children.

The Mahia Peninsula provided one of the more isolated groups which showed a marked difference between the older generation and the new. These people had good access to sea foods and those still using these abundantly had much the best teeth. A group of the children who had been born and raised in this district and who had lived largely on the native foods had only 1.7 per cent of their teeth attacked by dental caries.

The other places studied were Raukokore, Tekaha, Rautoki, Rotarua, Tehoro, Waiomio, Teahuahu, Kaikohe, Whakarara, Mautauri Bay, Ahipara, Manukau, Rawena, Ellerslie, Queen Victoria School at Auckland and Waipawa.

New Zealand has become justly famous for its scenery. The South Island has been frequently termed the Southern Alps because of its snow-capped mountains and glaciers. Of the 70,000 members of the Maori race living in the two islands, about 2000 are on the South Island and the balance on the North Island. While snow is present on many of the mountains of the North Island in the winter season, only a few of the higher peaks are snow capped during the summer. Most of the shoreline of the seacoast of the South Island is very rugged, with glaciers descending almost to the sea. The coastline of the North Island is broken and in places is quite rugged. The approach to the Mahia Peninsula is along a rocky coast skirting the bay. The most important industries of New Zealand are dairy products, and sheep raising for wool.

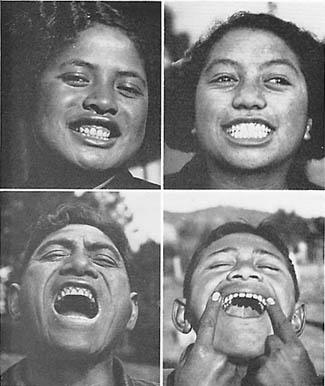

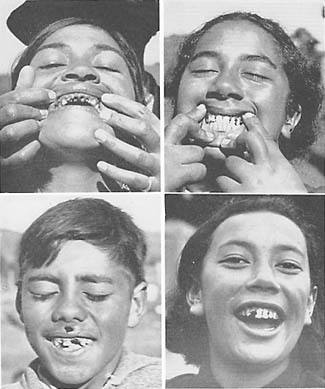

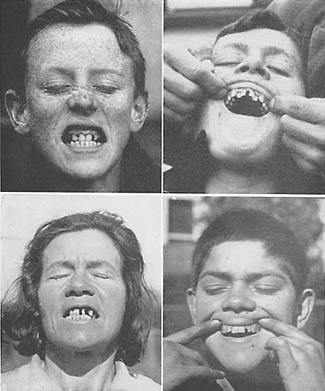

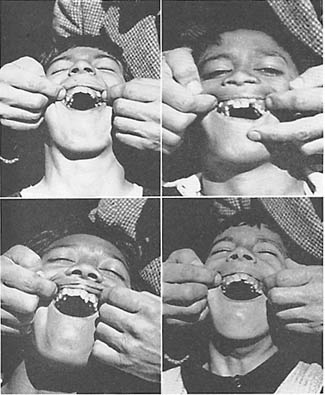

The reputation of the Maori people for splendid physiques has placed them on a pedestal of perfection. Much of this has been lost in modernization. However, through the assistance of the government, I was able to see many excellent physical specimens. In Fig. 69 will be seen four typical Maori who retained much of the tribal excellence. Note their fine dental arches. A young Maori man who stands about six feet four inches and weighs 230 pounds was examined. The Maori men have great physical endurance and good minds. Many fine lawyers and government executives are Maori. The breakdown of these people comes when they depart from their native foods to the foods of modern civilization, foods consisting largely of white flour, sweetened goods, syrup and canned goods. The effect is similar to that experienced by other races after using foods of modern civilization. Typical illustrations of tooth decay are shown in Fig. 70. In some individuals still in their teens half of the teeth were decayed. The tooth decay among the whites of New Zealand and Australia was severe. This is illustrated in Fig. 71. Particularly striking is the similarity between the deformities of the dental arches which occur in the Maori people who were born after their parents adopted the modern foods, and those of the whites. This is well illustrated in Fig. 72 for Maori boys. In my studies among other modernized primitive racial stocks, there was a very high incidence of facial deformity, which approached one hundred per cent among individuals in tuberculosis sanatoria. This condition obtained also in New Zealand.

|

| FIG. 69. Since the discovery of New Zealand the primitive natives, the Mann, have had the reputation of having the finest teeth and finest bodies of any race in the world. These faces are typical. Only about one tooth per thousand teeth had been attacked by tooth decay before they came under the influence of the white man. |

|

| FIG. 70. With the advent of the white man in New Zealand tooth decay has become rampant. The suffering from dental caries and abscessed teeth is very great in the most modernized Maori. The boy at the lower left has a deep scar in his upper lip from an accident. |

|

| FIG. 71. Whereas the original primitive Maori had reportedly the finest teeth in the world, the whites now in New Zealand are claimed to have the poorest teeth in the world. These individuals are typical. An analysis of the two types of food reveals the reason. |

|

| FIG. 72. In striking contrast with the beautiful faces of the primitive Maori those born since the adoption of deficient modernized foods are grossly deformed. Note the marked underdevelopment of the facial bones, one of the results being narrowing of the dental arches with crowding of the teeth and an underdevelopment of the air passages. We have wrongly assigned these distorted forms to mixture of racial bloods. |

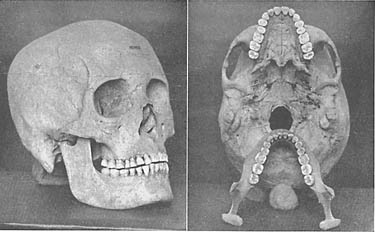

Through the kindness of the director of the Maori Museum at Auckland, I was able to examine many Maori skulls. Two views are shown in Fig. 73. The skulls belong in the pre-Columbian period. Note the splendid design of the face and dental arches and high perfection of the teeth.

|

| FIG. 73. The large collections of skulls of the ancient Mann of New Zealand attest to their superb physical development and to the excellence of their dental arches. |

One of the most important developments to come out of these investigations of primitive races is the evidence of a rapid decline in maternal reproductive efficiency after an abandonment of the native foods and the substitution of foods of modern civilization. This is discussed in later chapters.

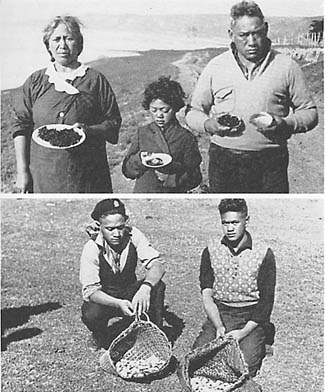

It was particularly instructive to observe the diligence with which some of the isolated Maori near the coast sought out certain types of food in accordance with the tradition and accumulated wisdom of their tribes. As among the various archipelagos and island dwellers of the Pacific, great emphasis was placed upon shell fish. Much effort was made to obtain these in large quantities. In Fig. 74 (lower), will be seen two boys who have been gathering sea clams found abundantly on these shores. Much of the fishing is done when the tide is out. Some groups used large quantities of the species called abalone on the West Coast of America and paua in New Zealand. In Fig. 74 (upper), a man, his wife and child are shown. The father is holding an abalone; the little girl is holding a mollusk found only in New Zealand, the toharoa; the mother is holding a plate of edible kelp which these people use abundantly, as do many sea bordering races. Maori boys enjoy a species of grubs which they seek with great eagerness and prize highly. The primitive Maori use large quantities of fern root which grows abundantly and is very nutritious.

|

| FIG. 74. Native Maori demonstrating some of the accessory essentials obtained from the sea. These include certain sea weeds and an assortment of shell fish. It is much easier for the moderns to exchange their labor for the palate tickling devitalized foods of commerce than to obtain the native foods of land and sea. |

Probably few primitive races have developed calisthenics and systematic physical exercise to so high a point as the primitive Maori. On arising early in the morning, the chief of the village starts singing a song which is accompanied by a rhythmic dance. This is taken up not only by the members of his household, but by all in the adjoining households until the entire village is swaying in unison to the same tempo. This has a remarkably beneficial effect in not only developing deep breathing, but in developing the muscles of the body, particularly those of the abdomen, with the result that these people maintain excellent figures to old age.

Sir Arbuthnot Lane (2) said of this practice the following:

As to daily exercise, it is shown here that every person capable of movement can benefit by it, and I am certain that the only natural and really beneficial system of exercise is that developed through long ages by the New Zealand Maori and their race-brothers in other lands.

The practical application of their wisdom is discussed in Chapter 21.

The Maori race developed a knowledge of Nature's laws and adopted a system of living in harmony with those laws to so high a degree that they were able to build what was reported by early scientists to be the most physically perfect race living on the face of the earth. They accomplished this largely through diet and a system of social organization designed to provide a high degree of perfection in their offspring. To do this they utilized foods from the sea very liberally. The fact that they were able to maintain an immunity to dental caries so high that only one tooth in two thousand had been attacked by tooth decay (which is probably as high a degree of immunity as that of any contemporary race) is a strong argument in favor of their plan of life.

REFERENCES

1. PICKERILL, H. P. The Prevention of Dental Caries and Oral Sepsis. Philadelphia, White, 1914.

2. LANE, A. Preface to Maori Symbolism by Ettie A. Rout. London, Paul Trench, Trubner, 1926.

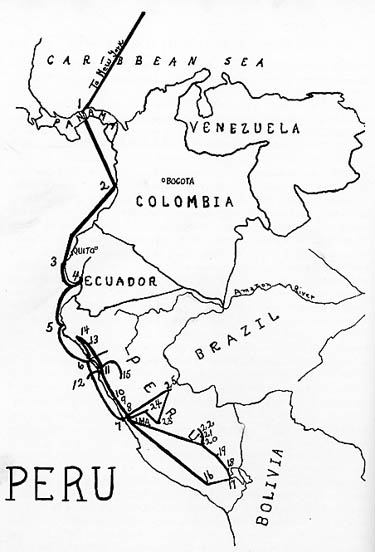

| Key to Route Followed in Peru | ||

| 1. Panama | 10. Huaura | 19. San Rosa |

| 2. Buenaventura | 11. Chimbote | 20. Cuzco |

| 3. Manta | 12. Santa Island | 21. Calca |

| 4. Guayaquil | 13. Chiclayo | 22. Manchu Piccu |

| 5. Talara | 14. Eten | 23. Huancayo |

| 6. Trujillo | 15. Huaraz | 24. Oroya |

| 7. Callao | 16. Arequipa | 25. Perene |

| 8. Lima | 17. Lake Titicaca | |

| 9. Huacho | 18. Juallanca |

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 13

ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS OF PERU

IN THE foregoing field studies among primitive races we have been dealing chiefly with living groups. Since the West Coast of South America has been the home of several ancient cultures, it is important that they be included with the living remnants of primitive racial stocks, in order to note the contributions that they may make to the problem of modern degeneration. The relationship between the Andes Mountain Range and the coast and the sea currents is such that there has been created a zone, ranging from forty to one hundred miles in width between the coast and the mountains, which for a distance of over a thousand miles is completely arid. The air currents drifting westward across South America from the Atlantic carry an abundance of moisture. When they strike the eastern foothills of the Andes they are projected upward into a region of constant cold which causes the moisture to be precipitated as rain on the eastern slopes, and as snow on the eastern Cordillera Range. Hence the name of the eastern range is the White Cordillera, and that of the western range, which receives little of this rain, is the Black Cordillera. Between these two ranges is a great plain, which in the rainy season is well watered. The great civilizations of the past have always utilized water from the melting snow through irrigation ditches with the result that a vast acreage was put to agricultural uses.

The Humboldt Current which sweeps northward from the southern ice fields and carries its chilly water almost to the equator has influenced the development of the West Coast of South America. The effect of the current on the climate is generally noticeable. One of the conspicuous results is the presence of a cloud bank which hovers over the coastal area at an altitude of from one thousand to three thousand feet above sea level for several months of the year. Back from the coast these clouds rest on the land and constitute a nearly constant fog for extended periods. When one passes inland from the coast up the mountains he moves from a zone which in winter is clammy and chilly, into the fog zone, and then suddenly out of it into clear sky and brilliant sunlight. It is of interest that the capital, Lima, is so situated that it suffers from this unhappy cloud and fog situation. When Pizarro sent a commission to search out a location for his capital city the natives commented on the fact that he was selecting a very undesirable location. Either on the coast or farther inland than Lima the climate is much more favorable, and these were the locations in which the ancient civilizations have left some very elaborate foundations of fortresses and extended residential areas. The great expanse of desert extending from the coast to the mountains, with its great moving sand dunes and with scarcely a sign of green life, is one of the least hospitable environments that any culture could choose. Notwithstanding this, the entire coast is a succession of ancient burial mounds in which it is estimated that there are fifteen million mummies in an excellent state of preservation. The few hundred thousand that have been disturbed by grave robbers in search of gold and silver, have been left bleaching on the sands. Where had these people come from and why were they buried here? The answer is to be found in the fact that probably few locations in the world provided such an inexhaustible supply of food for producing a good culture as did this area. The lack of present appreciation of this fact is evidenced by the absence of flourishing modern communities, notwithstanding the almost continuous chain of ancient walls, fortresses, habitations, and irrigation systems to be found along this coast. The Humboldt Current coming from the ice fields of the Antarctic carries with it a prodigious quantity of the chemical food elements that are most effective in the production of a vast population of fish. Probably no place in the world provides as great an area teeming with marine life. The ancient cultures appreciated the value of these sea foods and utilized them to the full. They realized also that certain land plants should be eaten with the sea foods. Accordingly, they constructed great aqueducts used in transporting the water, sometimes a hundred miles, for the purpose of irrigating river bottoms which had been collecting the alluvial soil from the Andes through past ages. These river beds are to be found from twenty to fifty miles apart and many of them are entirely dry except in the rainy season in the high Andes. In the river bottoms these ancient cultures grew large quantities of corn, beans, squash, and other plants. These plant foods were gathered, stored, and eaten with sea foods. The people on the coast had direct communication with the people in the high plateaus. It is of more than passing interest that some twenty-one of our modern food plants apparently came from Peru.

Where there is such a quantity of animal life in the sea in the form of fish one would expect to find the predatory animals that live on fish. One group of these attack the fish from the air and they constitute the great flock of guanayes, piqueros and pelicans. For a thousand miles along the coast, these fish-eating birds are to be seen in great winding queues going to and fro between the fishing grounds and their nesting places. At other times they may be seen in great clouds, beyond computation in number, fishing over an area of many square miles. On one island I was told by the caretaker that twenty-four million birds had their nests there. We passed through a flock of the birds fishing, which the caretaker estimated to contain between four and five million birds. On one island I found it impossible to step anywhere, off the path, without treading on birds' nests. It is of interest that a product of these birds has constituted one of the greatest sources of wealth in the past for Peru, namely, the guano, which is the droppings of the birds left on the islands along the coast where they have their nests. Through the centuries these deposits have reached to a depth of 100 feet in places. When it is realized that only one-fifth of the droppings are placed on the islands, it immediately raises the great question as to the quantity of fish consumed by these birds. As high as seventy-five fish have been found in the digestive tract of a single bird. The quantity of fish consumed per day by the birds nesting on this one island has been estimated to be greater than the entire catch of fish off the New England coast per day.

In addition to the birds, a vast number of sea lions and seals live on the fish. The sea lions have a rookery in the vicinity of Santa Island, which was estimated to contain over a million. These enormous animals devour great quantities of fish. It would be difficult to estimate how far the fish destroyed by this one group of sea lions would go toward providing excellent nutrition for the entire population of the United States. The guano, consisting of the partially digested animal life of the sea, constitutes what is probably the best known fertilizer in the world. It is thirty-three times as efficient as the best barnyard manure. At one time it was sent in shiploads to Europe and the United States, but now the Peruvian Government is retaining nearly all of it for local use. They have locked the barn door after the horse was stolen, figuratively speaking, since the accumulation of ages had been carried off by shiploads to other countries before its export was checked. At the present time all islands are under guard and the birds are protected. They are coming back into many of the islands from which they had been driven and are re-nesting. Birds are given two or three years of undisturbed life for producing deposits. These are then carefully removed from the surface of the islands and the birds are allowed to remain undisturbed for another period.

A very important and fortunate phase of the culture of the primitive races of the coast has been their method of burial. Bodies are carefully wrapped in many layers of raiment often beautifully spun. With the mummies articles of special interest and value are usually buried. Implements used by the individuals in their lifetime were also put in the grave. With a fisherman there were placed his nets and fishing tackle. Almost always, jars containing foods to supply him on his journey in the transition to a future life were left in the tomb. In some of the cultures the various domestic and industrial scenes were reproduced in pottery. These disclosed a great variety of foods which are familiar to us today. Even the designs of their habitations were reproduced in pottery. Similarly their methods of performing surgical operations, in which they were very skillful, were depicted. Fortunately, the different cultures had quite different types of pottery as well as quite different types of clothing. This makes it possible to identify various groups and indicate the boundaries of their habitations.

Не нашли, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском: