ТОР 5 статей:

Методические подходы к анализу финансового состояния предприятия

Проблема периодизации русской литературы ХХ века. Краткая характеристика второй половины ХХ века

Характеристика шлифовальных кругов и ее маркировка

Служебные части речи. Предлог. Союз. Частицы

КАТЕГОРИИ:

- Археология

- Архитектура

- Астрономия

- Аудит

- Биология

- Ботаника

- Бухгалтерский учёт

- Войное дело

- Генетика

- География

- Геология

- Дизайн

- Искусство

- История

- Кино

- Кулинария

- Культура

- Литература

- Математика

- Медицина

- Металлургия

- Мифология

- Музыка

- Психология

- Религия

- Спорт

- Строительство

- Техника

- Транспорт

- Туризм

- Усадьба

- Физика

- Фотография

- Химия

- Экология

- Электричество

- Электроника

- Энергетика

4 страница. From Grachen we returned to St

From Grachen we returned to St. Nicholas and proceeded from there by train down the valley and up another steep ascent, requiring several hours, to the hamlet of Visperterminen, on the east side of the mountain above the Visp River, and below the junction of the Mattervisp and Saaservisp. This community is made up of about 1,600 people living on a sheltered shelf high above the river valley. The view from this position is indescribably beautiful. It is a little below the timber line of this and the surrounding mountains. Majestic snow-clad peaks and precipitous mountains dot the horizon and shade off into winding gorges which mark the course of wandering streams several thousand feet below our vantage point. It is a place to stop and ponder.

The gradations in climate range in the summer from a tropical temperature in protected nooks during the daytime to sub-zero weather with raging blizzards at night on the high mountains. It is a place where human stamina can be tempered to meet all the vicissitudes of life.

The village consists of a group of characteristically designed Swiss chalets clustered on the mountain side. The church stands out as a beacon visible from mountains in all directions. Visperterminen is unique in many respects. Notwithstanding its relative proximity to civilization--it is only a few hours' journey to the thoroughfare of the Rhone Valley--it has enjoyed isolation and opportunity for maintaining its characteristic primitive social and civil life. We were greeted here by the president of the village who graciously opened the school house and sent messengers to have the children of the community promptly come to the school building in order that we might make such studies as we desired. This study included a physical examination of the teeth and of the general development of the children, particularly of the faces and dental arches, the making of photographic records, the obtaining of samples of saliva, as in other places, and also the making of a detailed study of the nutrition. In addition, we obtained samples of foods for chemical analysis.

The people of Visperterminen have the unique distinction of owning land in the lower part of the mountain on which they maintain vineyards to supply wine for this country. They have the highest vineyards of Europe. They are grown on banks that are often so steep that one wonders how the tillers of the soil or the gatherers of the fruit can maintain their hold on the precarious and shifting footing. Each terrace has a trench near its lower retaining wall to catch the soil that is washed down, and this soil must be carried back in baskets to the upper boundary of the plot. This is all done by human labor. The vineyards afforded them the additional nutrition of wine and of fruit minerals and vitamins which the two groups we studied at Loetschental and Grachen did not have.

This additional nutrition was of importance because of the opportunity for obtaining through it vitamin C. It is of particular interest in the study of the incidence of tooth decay in Visperterminen that these additional factors had not created a higher immunity to tooth decay, nor a better condition of health in gingival tissues than previously found. In each one hundred teeth examined 5.2 were found to have been attacked at some time by tooth decay. Here again the nutrition consisted of rye, used almost exclusively as the cereal; of dairy products; of meat about once a week; and also some potatoes. Limited green foods were eaten during the summer. The general custom is to have a sheep dressed and distributed to a group of families, thus providing each family with a ration of meat for one day a week, usually Sunday. The bones and scraps are utilized for making soups to be served during the week. The children have goat's milk in the summer when the cows are away in the higher pastures near the snow line. Certain members of the families go to the higher pastures with the cows to make cheese for the coming winter's use.

The problem of identifying goats or cattle for establishing individual ownership is a considerable one where the stock of all are pastured in common herds. It was interesting to us to observe how this problem was met. The president of the village has what is called a "tessel" which is a string of manikins in imitation of goats or cattle made of wood and leather. Every stock owner must provide a manikin to be left in the safekeeping of the president of the village with whom it is registered. It carries on it the individual markings that this member of the colony agrees to put on every member of his animal stock. The marking may be a hole punched in the left ear or a slit in the right ear, or any combination of such markings as is desired. Thereafter all animals carrying that mark are the property of the person who registered it; similarly, any animals that have not this individual symbol of identification cannot be claimed by him.

As one stands in profound admiration before the stalwart physical development and high moral character of these sturdy mountaineers, he is impressed by the superior types of manhood, womanhood, and childhood that Nature has been able to produce from a suitable diet and a suitable environment. Surely, here is evidence enough to answer the question whether cereals should be avoided because they produce acids in the system which if formed will be the cause of tooth decay and many other ills including the acidity of the blood or saliva. Surely, the ultimate control will be found in Nature's laboratory where man has not yet been able to meddle sufficiently with Nature's nutritional program to blight humanity with abnormal and synthetic nutrition. When one has watched for days the childlife in those high Alpine preserves of superior manhood; when one has contrasted these people with the pinched and sallow, and even deformed, faces and distorted bodies that are produced by our modern civilization and its diets; and when one has contrasted the unsurpassed beauty of the faces of these children developed on Nature's primitive foods with the varied assortment of modern civilization's children with their defective facial development, he finds himself filled with an earnest desire to see that this betterment is made available for modern civilization.

Again and again we had the experience of examining a young man or young woman and finding that at some period of his life tooth decay had been rampant and had suddenly ceased; but, during the stress, some teeth had been lost. When we asked such people whether they had gone out of the mountain and at what age, they generally replied that at eighteen or twenty years of age they had gone to this or that city and had stayed a year or two. They stated that they had never had a decayed tooth before they went or after they returned, but that they had lost some teeth in the short period away from home.

At this point of our studies Dr. Roos found it necessary to leave, but Dr. Gysi accompanied us to the Anniviers Valley, which is also on the south side of the Rhone. The river of the valley, the Navizenze, drains from the high Swiss and Italian boundary north to the Rhone River. Here again we had the remarkable experience of finding communities near to each other, one blessed with high immunity to tooth decay, and the other afflicted with rampant tooth decay.

The village of Ayer lies in a beautiful valley well up toward the glaciers. It is still largely primitive, although a government road has recently been developed, which, like many of the new arteries, has made it possible to dispatch military protection when and if necessary to any community. In this beautiful hamlet, until recently isolated, we found a high immunity to dental caries. Only 2.3 teeth out of each hundred examined were found to have been attacked by tooth decay. Here again the people were living on rye and dairy products. We wonder if history will repeat itself in the next few years and if there, too, this enviable immunity will be lost with the advent of the highway. Usually it is not long after tunnels and roads are built that automobiles and wagons enter with modern foods, which begin their destructive work. This fact has been tragically demonstrated in this valley since a roadway was extended as far as Vissoie several years ago. In this village modern foods have been available for some time. One could probably walk the distance from Ayer to Vissoie in an hour. The number of teeth found to be attacked with caries for each one hundred children's teeth examined at Vissoie was 20.2 as compared with 2.3 at Ayer. We had here a splendid opportunity to study the changes that had occurred in the nutritional programs. With the coming of transportation and new markets there had been shipped in modern white flour; equipment for a bakery to make white-flour goods; highly sweetened fruit, such as jams, marmalades, jellies, sugar and syrups--all to be traded for the locally produced high-vitamin dairy products and high-mineral cheese and rye; and with the exchange there was enough money as premium to permit buying machine-made clothing and various novelties that would soon be translated into necessities.

Each valley or village has its own special feast days of which athletic contests are the principal events. The feasting in the past has been largely on dairy products. The athletes were provided with large bowls of cream as constituting one of the most popular and healthful beverages, and special cheese was always available. Practically no wine was used because no grapes grew in that valley, and for centuries the isolation of the people prevented access to much material that would provide wine. In the Visperterminen community, however, the special vineyards owned by these people on the lower level of the mountain side provided grape juice in various stages of fermentation, and their feasts in the past have been celebrated by the use of wines of rare vintage as well as by the use of cream and other dairy products. Their cream products took the place of our modern ice cream. It was a matter of deep interest to have the President of Visperterminen show us the tankards that had been in use in that community for nine or ten centuries. The care of these was one of the many responsibilities of the chief executive of the hamlet.

It is reported that practically all skulls that are exhumed in the Rhone valley, and, indeed, practically throughout all of Switzerland where graves have existed for more than a hundred years, show relatively perfect teeth; whereas the teeth of people recently buried have been riddled with caries or lost through this disease. It is of interest that each church usually has associated with it a cemetery in which the graves are kept decorated, often with beautiful designs of fresh or artificial flowers. Members of succeeding generations of families are said to be buried one above the other to a depth of many feet. Then, after a sufficient number of generations have been so honored, their bodies are exhumed to make a place for present and coming generations. These skeletons are usually preserved with honor and deference. The bones are stacked in basements of certain buildings of the church edifice with the skulls facing outward. These often constitute a solid wall of considerable extent. In Naters there is such a group said to contain 20,000 skeletons and skulls. These were studied with great interest as was also a smaller collection in connection with the cathedral at Visp. While many of the single straight-rooted teeth had been lost in the handling, many were present. It was a matter of importance to find that only a small percentage of teeth had had caries. Teeth that had been attacked with deep caries had developed apical abscesses with consequent destruction of the alveolar processes. Evidence of this bone change was readily visible. Sockets of missing teeth still had continuous walls, indicating that the teeth had been vital at death.

The reader will scarcely believe it possible that such marked differences in facial form, in the shape of the dental arches, and in the health condition of the teeth as are to be noted when passing from the highly modernized lower valleys and plains country in Switzerland to the isolated high valleys can exist. Fig. 3 shows four girls with typically broad dental arches and regular arrangement of the teeth. They have been born and raised in the Loetschental Valley or other isolated valleys of Switzerland which provide the excellent nutrition that we have been reviewing. They have been taught little regarding the use of tooth brushes. Their teeth have typical deposits of unscrubbed mouths; yet they are almost completely free from dental caries, as are the other individuals of the group they represent. In a study of 4,280 teeth of the children of these high valleys, only 3.4 per cent were found to have been attacked by tooth decay. This is in striking contrast to conditions found in the modernized sections using the modern foods.

|

| FIG. 3. Normal design of face and dental arches when adequate nutrition is provided for both the parents and the children. Note the well developed nostrils. |

In Loetschental, Grachen, Visperterminen and Ayer, we have found communities of native Swiss living almost exclusively on locally produced foods consisting of the cereal, rye, and the animal product, milk, in its various forms. At Vissoie, with its available modern nutrition, there has been a complete change in the level of immunity to dental caries. It is important that studies be made in other communities which correspond in altitude with the first four places studied in which there was a high immunity to dental caries. Modern foods should be available in the new communities selected for comparative study. To find such places one would naturally think of those that are world-famed as health resorts providing the best things that modern science and industry can assemble. Surely St. Moritz would be such a place. It is situated in the southeastern part of the Republic of Switzerland near the headwaters of the Danube in the upper Engadin. This world-famous watering place attracts people of all continents for both summer and winter health building and for the enjoyment of the mountain lakes, snow-capped peaks, forested mountain sides, and crystal clear atmosphere with abundance of sunshine.

The journey from the Canton of Wallis (Valais) to the upper Engadin takes one up the Rhone valley, climbing continually to get above cascades and beautiful waterfalls until one comes to the great Rhone glacier which blocks the end of the valley. The water gushes from beneath the mountain of ice to become the parent stream of the Rhone river which passes westward through the Rhone valley receiving tributaries from snow-fed streams from both north and south watersheds, as it rolls westward to the beautiful Lake Geneva and then onward west and south to the Mediterranean.

It is of significance that a study of the child life in the Rhone valley, as made by Swiss officials and reported by Dr. Adolf Roos and his associates, shows that practically every child had tooth decay and the majority of the children had decay in an aggravated form. People of this valley are provided with adequate railroad transportation for bringing them the luxuries of the world. As we pass eastward over the pass through Andermatt, we are reminded that the trains of the St. Gotthard tunnel go thundering through the mountain a mile below our feet en route to Italy. To reach our goal, the beautiful modern city and summer resort of St. Moritz, we enter the Engadin country famed for its beauty and crystal-clear atmosphere. We already know something of the beauty that awaits us which has attracted pleasure seekers and beauty lovers of the world to St. Moritz. One would scarcely expect to see so modern a city as St. Mortiz at an altitude of a little over a mile, with little else to attract people than its climate in winter and summer, the magnificent scenery, and the clear atmosphere. We have passed from the communities where almost everyone wears homespuns to one of English walking coats and the most elegant of feminine attire. Everyone shows the effect of contact with culture. The hotels in their appointments and design are reminiscent of Atlantic City. Immediately one sees something is different here than in the primitive localities: the children have not the splendidly developed features, and the people give no evidence of the great physical reserve that is present in the smaller communities.

Through the kindness of Dr. William Barry, a local dentist, and through that of the superintendent of the public schools, we were invited to use one of the school buildings for our studies of the children. The summer classes were dismissed with instructions that the children be retained so that we could have them for study. Several factors were immediately apparent. The teeth were shining and clean, giving eloquent testimony of the thoroughness of the instructions in the use of the modern dentifrices for efficient oral prophylaxis. The gums looked better and the teeth more beautiful for having the debris and deposits removed. Surely this superb climate, this magnificent setting, combined with the best of the findings of modern prophylactic science, should provide a 100-per-cent immunity to tooth decay. But in a study of the children from eight to fifteen years of age, 29.8 per cent of the teeth had already been attacked by dental caries. Our study of each case included careful examining of the mouth; photographing of the face and teeth; obtaining of samples of saliva for chemical analysis; and a study of the program of nutrition followed by the given case. In most cases, the diet was strikingly modern, and the only children found who did not have tooth decay proved to be children who were eating the natural foods, whole rye bread and plenty of milk.

In Chapter 15, a detailed discussion of the chemical differences in the food constituents is presented for both the districts subject to immunity, and for those subject to susceptibility.

I was told by a former resident of this upper Engadin country that in one of the isolated valleys only a few decades ago the children were still carrying their luncheons to school in the form of roasted rye carried dry in their pockets. Their ancestors had eaten cereal in this dry form for centuries.

St. Moritz is a typical Alpine community with a physical setting lar to that in the Cantons of Bern and Wallis (Valais). It is, however, provided with modern nutrition consisting of an abundance of white-flour products, marmalades, jams, canned vegetables, confections, and fruits--all of which are transported to the district. Only a limited supply of vegetables is grown locally. We studied some children here whose parents retained their primitive methods of food selection, and without exception those who were immune to dental caries were eating a distinctly different food from those with high susceptibility to dental caries.

Few countries of the world have had officials so untiring in their efforts to study and tabulate the incidence of dental caries in various geographic localities as has Switzerland. In the section lying to the north and east, and near Lake Constance, there is a considerable district where it is reported that 100 per cent of the people are suffering from dental caries. In almost all the other parts of Switzerland in which the population is large 95 to 98 per cent of the people suffer from dental caries. Of the two remaining districts, in one there is from 90 to 95 per cent and in the other from 85 to 90 per cent individual susceptibility to dental caries. Since in the district in the vicinity of Lake Constance the incidence of dental caries is so high that it is recorded as 100 per cent, it seemed especially desirable to make a similar critical study there and to obtain samples of saliva and detailed information regarding the food, and to make detailed physical examinations of growing children in this community, and through the great kindness of Dr. Hans Eggenberger, Director of Public Health for this general district, we were given an opportunity to do so.

Arrangements were made by Dr. Eggenberger so that typical groups of children, some in institutions, could be studied. He is located at Herisau in the Canton of St. Gall. We found work well organized for building up the health of these children in so far as outdoor treatment, fresh air, and sunshine were concerned. As dental caries is a major problem, and probably nutritional, it is treated by sunshine. The boys' group and girls' group are both given suitable athletic sports under skillfully trained directors. These groups are located in different parts of the city. Their recreation grounds are open lawns adjoining wooded knolls which give the children protection and isolation in which to play in their sunsuits and build vigorous appetites, and thus to prepare for their institutional foods which were largely from a modern menu. Critical dental examinations were made and an analysis of the data obtained revealed that one-fourth of all teeth of these growing boys and girls had already been attacked by dental caries, and that only 4 per cent of the children had escaped from the ravages of tooth decay, which disease many of them had in an aggravated form.

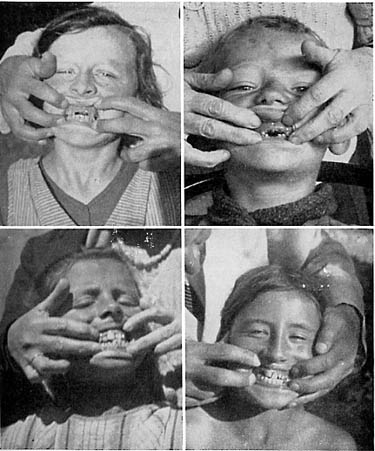

In the Herisau group 25.5 per cent of the 2,065 teeth examined had been attacked by dental caries and many teeth were abscessed. The upper photographs in Fig. 4 are of two girls with typically rampant tooth decay. The one to the left is sixteen years of age and several of her permanent teeth are decayed to the gum line. Her appearance is seriously marred, as is also that of the girl to the right.

Another change that is seen in passing from the isolated groups with their more nearly normal facial developments, to the groups of the lower valleys, is the marked irregularity of the teeth with narrowing of the arches and other facial features. In the lower half of Fig. 4 may be seen two such cases. While in the isolated groups not a single case of a typical mouth breather was found, many were seen among the children of the lower-plains group. The children studied were from ten to sixteen years of age.

|

| Fig. 4. In the modernized districts of Switzerland tooth decay is rampant. The girl, upper left, is sixteen and the one to the right is younger. They use white bread and sweets liberally. The two children below have very badly formed dental arches with crowding of the teeth. this deformity is not due to heredity. |

Many individuals in the modernized districts bore on their faces scars which indicated that the abscess of an infected tooth had broken through to the external surface where it had developed a fistula with resultant scar tissue, thus producing permanent deformity.

Bad as these conditions were, we were told that they were better than the average for the community. The ravages of dental caries had been strikingly evident as we came in contact with the local and traveling public. As we had at St. Moritz, we found an occasional child with much better teeth than the average. Usually the answer was not far to seek. For example, in one of the St. Moritz groups, in a class of sixteen boys, there were 158 cavities, or an average of 9.8 cavities per person (fillings are counted as cavities). In the cases of three other children in the same group, there were only three cavities, and one case was without dental caries. Two of these three had been eating dark bread or entire-grain bread, and one was eating dark bread and oatmeal porridge. All three drank milk liberally.

When looking here for the source of dairy products one is impressed by the absence of cows at pasture in the plains of Switzerland, areas in which a large percentage of the entire population resides. True, one frequently sees large laiteries or creameries, but the cows are not in sight. On asking the explanation for this, I found that a larger quantity of milk could be obtained from the cows if they were kept in the stables during the period of high production. Indeed, this was a necessity in most of these communities since there were so few fences, and during the time of the growth of the crops, including the stock feed for the winter's use, it was necessary that the cows be kept enclosed. About the only time that cows were allowed out on pasture was in the fall after the crops had been harvested and while the stubble was being plowed.

Among the children in St. Moritz and Herisau, those groups with the lower number of cavities per person were using milk more or less liberally. Of the total number of children examined in both places only 11 per cent were using milk in their diets, whereas 100 per cent of the children in the other districts that provided immunity were using milk. Nearly every child in St. Moritz was eating white bread. In Herisau, all but one of the children examined were eating white bread in whole or in principal part.

Since so many cattle were stall-fed in the thickly populated part of Switzerland, and since so low a proportion of the children used milk even sparingly, I was concerned to know what use was made of the milk. Numerous road signs announcing the brand of sweetened milk chocolate made in the several districts suggested one use. This chocolate is one of the important products for export and as a beverage constitutes a considerable item in the nutrition of large numbers living in this and in other countries. It is recognized as a high source of energy, primarily because of the sugar and chocolate which when combined with the milk greatly reduces the ratio of the minerals to the energy factors as expressed in calories.

It was formerly thought that dental caries which was so rampant in the greater portion of Switzerland was due in part to low iodine content in the cattle feed and in other food because of iodine deficiency in the soil. Large numbers of former generations suffered from clinical goiter and various forms of thyroid disturbances. That this is not the cause seems clearly demonstrated by the fact that dental caries is apparently as extensive today as ever before, if not more so, while the iodine problem has been met through a reinforcement of the diet of growing children and others in stress periods with iodine in suitable form. Indeed the early work done in Cleveland by Crile, Marine, and Kimball was referred to by the medical authorities there as being the forerunner of the control of the thyroid disorder in these communities.

The officials of the Herisau community were so deeply concerned regarding the prevalence of dental caries that they were carrying forward institutional and community programs with the hope of checking this affliction. If dental caries were primarily the result of an inadequate amount of vitamin D, then sunning the patients should provide an adequate reinforcement. This is one of the principal purposes for getting the growing boys and girls of the community into sunsuits for tanning their bodies.

Another procedure to which my attention was called consisted of adding to the bread a product high in lime, which was being obtained in the foothills of the district. This and other types of bread were studied by chemical analyses. Clinically, tooth decay was not reduced.

I made an effort to establish a clinic in a neighboring town for the purpose of demonstrating with a group of children that dental caries can be controlled by a simple nutritional program. An interesting incident developed in connection with the selection of the children for this experimental group. When parents were asked to permit their children to have one meal a day reinforced, according to a program that has proved adequate with my clinical groups in Cleveland, the objection was made that there was no use trying to save the teeth of the girls. The girls should have all their teeth extracted and artificial teeth provided before they were married, because if they did not they would lose them then.

It is of interest that the southern part of Switzerland including the high Alpine country is largely granite. The hills in the northern part of Switzerland are largely limestone in origin. A great number of people live in the plain between these two geologic formations, a plain which is largely made of alluvial deposits which have been washed down from the upper formations. The soil is extraordinarily fertile soil and has supported a thrifty and healthy population in the past.

When I asked a government official what the principal diseases of the community were, he said that the most serious and most universal was dental caries, and the next most important, tuberculosis; and that both were largely modern diseases in that country.

When I visited the famous advocate of heliotherapy, Dr. Rollier, in his clinic in Leysin, Switzerland, I wondered at the remarkable results he was obtaining with heliotherapy in nonpulmonary tuberculosis. I asked him how many patients he had under his general supervision and he said about thirty-five hundred. I then asked him how many of them come from the isolated Alpine valleys and he said that there was not one; but that they were practically all from the Swiss plains, with some from other countries.

Не нашли, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском: