ÒÎÐ 5 ñòàòåé:

Ìåòîäè÷åñêèå ïîäõîäû ê àíàëèçó ôèíàíñîâîãî ñîñòîÿíèÿ ïðåäïðèÿòèÿ

Ïðîáëåìà ïåðèîäèçàöèè ðóññêîé ëèòåðàòóðû ÕÕ âåêà. Êðàòêàÿ õàðàêòåðèñòèêà âòîðîé ïîëîâèíû ÕÕ âåêà

Õàðàêòåðèñòèêà øëèôîâàëüíûõ êðóãîâ è åå ìàðêèðîâêà

Ñëóæåáíûå ÷àñòè ðå÷è. Ïðåäëîã. Ñîþç. ×àñòèöû

ÊÀÒÅÃÎÐÈÈ:

- Àðõåîëîãèÿ

- Àðõèòåêòóðà

- Àñòðîíîìèÿ

- Àóäèò

- Áèîëîãèÿ

- Áîòàíèêà

- Áóõãàëòåðñêèé ó÷¸ò

- Âîéíîå äåëî

- Ãåíåòèêà

- Ãåîãðàôèÿ

- Ãåîëîãèÿ

- Äèçàéí

- Èñêóññòâî

- Èñòîðèÿ

- Êèíî

- Êóëèíàðèÿ

- Êóëüòóðà

- Ëèòåðàòóðà

- Ìàòåìàòèêà

- Ìåäèöèíà

- Ìåòàëëóðãèÿ

- Ìèôîëîãèÿ

- Ìóçûêà

- Ïñèõîëîãèÿ

- Ðåëèãèÿ

- Ñïîðò

- Ñòðîèòåëüñòâî

- Òåõíèêà

- Òðàíñïîðò

- Òóðèçì

- Óñàäüáà

- Ôèçèêà

- Ôîòîãðàôèÿ

- Õèìèÿ

- Ýêîëîãèÿ

- Ýëåêòðè÷åñòâî

- Ýëåêòðîíèêà

- Ýíåðãåòèêà

Articles and Essays 2 ñòðàíèöà

Harry Richardson and Clare Page of Committee

Harry Richardson and Clare Page of Committee

Kebab Lamp, "Sleep", 2005 Designed and Produced by Committee

Kebab Lamp, "Sleep", 2005 Designed and Produced by Committee

Kabab Lamp, "Mountain Rescue", 2005 Designed and Produced by Committee

Kabab Lamp, "Mountain Rescue", 2005 Designed and Produced by Committee

Kabab Lamp, "Turtle Soup", 2005 Designed and Produced by Committee

Kabab Lamp, "Turtle Soup", 2005 Designed and Produced by Committee

Kabab Lamp, "Disco Rabbit", 2005 Designed and Produced by Committee

Kabab Lamp, "Disco Rabbit", 2005 Designed and Produced by Committee

Kebab Lamp, "Slipper", 2005 Designed and Produced by Committee

Kebab Lamp, "Slipper", 2005 Designed and Produced by Committee

Origami Desk, 2005 Designed and Produced by Committee

Origami Desk, 2005 Designed and Produced by Committee

Flytip Wallpaper, 2005 Designed and Produced by Committee

Flytip Wallpaper, 2005 Designed and Produced by Committee

| Article 5. Committee Product Designers (1975- + 1975-) Design Mart - Design Museum Exhibition 14 January to 19 February 2006 The raw material of the lighting and wallpaper designed by Clare Page (1975-) and Harry Richardson (1975-), who work together as COMMITTEE, is the junk that they find in the flytips and skips and on the market stalls and streets in Deptford, the area of south east London where they live and work. At first glance the colourful assortment of pottery animals, vases, figurines, boxes and other bric-a-brac clinging to Committee’s Kebab Lamps looks like a cheerful jumble of random objects. Gradually it becomes clear that the choice was painstakingly considered, and that Clare Page and Harry Richardson, co-founders of Committee, spend days finessing sequences of objects to explore a theme or to tell a story. Most of the objects come from the junk stalls on Deptford Market, a short walk from their studio, and arrived there from the local tip. Born in Northampton and London respectively in 1975, Page and Richardson moved to Deptford in 1998 after graduating in fine art from Liverpool Art School. Since founding Committee in 2001, they have worked as designers applying “pragmatism and imagination” to exploring “the drama of the everyday”. Having transformed tip cast-offs into desirable objects in their Kebab Lamps, the pair collaged images of more junk salvaged from tips and on the streets into the Flytip wallpaper commissioned for the British Council's exhibition My World, 2005. “Looking at these objects, it isn’t clear if they are beautiful and noble on their way up to the heavenly rubbish dump in the sky,” they observed, “or a chintzy portrayal of excessive consumption.” Q. How did you both first become interested in design? A. As children we both used to draw things all the time and were particularly fussy about our clothes; so maybe an interest has always been there. Q. Why did you decide to work as designers having originally studied fine art? How do you define the distinction between design and art? And how is it evolving? A. In our experience, each and every discipline relating to visual culture requires a very similar, complex questioning of motives and outcomes if you wish to fully understand what the use, purpose and meaning of the work might be. Is the chair/sculpture/dress meant for sitting on; to be a thing of beauty; to be displayed in a glass box; to save materials; to declare your status; to last a long time; to be affordable; to make someone money; to prompt dialogue, to make you laugh or to be a cocktail of the above? Now that technology has the potential to provide for most of our material needs and the whole art thing collapsed under the weight of a urinal some time ago, it seems to us that what remains is perhaps what, behind the modernist assumptions, has always been; a ‘free for all’ manipulation of aesthetics. Both artists and designers engage in this manipulation for a variety of personal and commercial reasons and the results are more often than not related to, or harnessed into a particular industry whose activities largely define how we view the result. So with that creative cat out of the bag, animators become advertisers, artists design restaurant interiors and product designers exhibit unusable items in galleries and it seems clear we shouldn’t rely on any of the old job descriptions, nor some of the accompanying institutions, to define the boundaries between these disciplines anymore. Perhaps that is just as it should be, however it raises the question of how we find and define quality and what as designers and artists we actually strive for in our manipulations. This question is pressing given that a distinguishing feature of our time is the eagerness of artists and designers (now seldom tethered to any craft) to cross the apparent boundaries just for the sake of it, with the resulting transgression being applauded as an end in itself. Our own interest in design is prompted by how powerfully the functionality and appearance of the material world affects our existence, (as the Victorian writer Mrs C. F. Forbes once said: "The sense of being well-dressed gives a feeling of inward tranquillity which religion is powerless to bestow.") But our material world is now almost entirely influenced by commercial factors of an impersonal kind, which don’t necessarily encourage the qualitative judgments that might be hoped for. Of course we don’t expect to have any definitive answers, but we are nevertheless drawn to being involved with that problem. Q. What are your objectives as designers? A. To be completely honest, we are not sure of the answer to this question. In general our objectives are many and changeable from job to job and therefore hard to declare. We also think it can take a long time to fully understand one’s objectives, maybe a lifetime, and there is probably a wisdom in trying not to pin them down, in order to stay innovative. Q. How did the Kebab Lamp develop? And how do you envisage it developing in future? A. The drama of the everyday is an important theme for us, and the Kebab Lamp explores the possibility of making a spectacle of attractive qualities out of the random and ordinary. Each one is hopefully a celebration of the very human instinct to aspire to the absolutes of beauty, elegance and sexiness from the jumble of everyday existence. Q. How did the Origami Desk develop? A. This was really a little exercise in colour and efficiency. Q. And the Flytip wallpaper? A. As designers of material things it is hard to avoid the thought that your work is part of the engine that drives humanity’s creation of material waste. However we do enjoy the wonder and pleasure that is designed into material things and have a strong respect for that wonder (having experienced many great love affairs with apparently small and insignificant objects). With this in mind, the wallpaper was produced with a desire to depict the tragic last dance of discarded objects, whipped up into a confection of items to be enjoyed for the last time before disappearing into uselessness. As we look at these objects in suspension, it is uncertain if they are beautiful and noble, on their way up to the heavenly rubbish dump in the sky after a life of service, or whether they are a saccharine, chintzy portrayal of our excessive consuming, about to crash back down to earth. Q. What would you identify as the defining qualities of your work? A. Pragmatism and imagination: in fitting proportions. At least that is what we aspire to. This may not be obvious from the appearance of our work, especially regarding the Kebab Lamp, but on the pole of a standard lamp we identified a place where a great deal of apparently excessive decoration and detail could be enjoyed that, most importantly, did not interfere with the functionality of the item and secondly did not produce any unnecessary waste, since it reuses already redundant pieces. Q. How important is the process of making your work to you? A. In light of the above statement, it is important if we are making something that requires our personal input to give it merit. In the case of the Kebab Lamp that is vital, as one of its ‘uses’ is to present humour, dialogue and hand made detail that is generated by us, through each composition. However for a design that does not require that input to produce its quality then we don’t mind who makes it, so long as the process suits the end product. Q. Do you consider your work to be part of a tradition? A. A truthful answer to this question is that as designers we feel like children of a tradition-less time, simply responding to a great love for the world. However if a tradition was something one could choose, a light hearted answer would be that we’d quite like our work to follow in the footsteps of a Dada sound poem, nodding in passing to the Bauhaus, while wearing some Versace. © Design Museum |

Concorde in flight British Aircraft Corporation/Aerospatiale © British Airways Plc.

Concorde in flight British Aircraft Corporation/Aerospatiale © British Airways Plc.

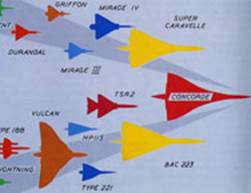

The Concorde 'family tree' illustrating how the development of different jets contributed to that of Concorde

The Concorde 'family tree' illustrating how the development of different jets contributed to that of Concorde

Diagram showing the distribution of responsibilities for the development of Concorde between the British Aerospace Corporation and Aerospatiale and, for the engine, Rolls-Royce and SNECMA

Diagram showing the distribution of responsibilities for the development of Concorde between the British Aerospace Corporation and Aerospatiale and, for the engine, Rolls-Royce and SNECMA

Concorde's Rolls-Royce/SNECMA Olympus 593-610 engine

Concorde's Rolls-Royce/SNECMA Olympus 593-610 engine

Concorde 002 arriving at Fairford at the end of her maiden flight on 9 April 1969

Concorde 002 arriving at Fairford at the end of her maiden flight on 9 April 1969

Brian Trubshaw and John Cochrane, the pilots of the first test flight of Concorde 002 on 9 April 1969

Brian Trubshaw and John Cochrane, the pilots of the first test flight of Concorde 002 on 9 April 1969

Concorde on the ground at Waco, Texas, June 1986 © Christopher Orlebar

Concorde on the ground at Waco, Texas, June 1986 © Christopher Orlebar

Concorde in flight © Christopher Orlebar

Concorde in flight © Christopher Orlebar

Concorde maintenance engineers at work at Heathrow Airport, London © Christopher Orlebar

Concorde maintenance engineers at work at Heathrow Airport, London © Christopher Orlebar

The maintenance of a British Airways Concorde at Heathrow Airport, London © Christopher Orlebar

The maintenance of a British Airways Concorde at Heathrow Airport, London © Christopher Orlebar

Concorde in flight, November 1985.

Concorde in flight, November 1985.

Concorde G-BOAG, the Red Arrows and the QE2 flying over the English Channel, summer 1985

Concorde G-BOAG, the Red Arrows and the QE2 flying over the English Channel, summer 1985

| Article 6 Concorde Supersonic Passenger Aircraft (1976-2003) Designing Modern Britain - Design Museum Until 26 November 2006 One of the best-loved engineering design projects of the 20th century, CONCORDE (1976-2003) is a rare example of successful international collaboration. Its Anglo-French designers produced the world’s first supersonic commercial passenger aircraft which at its fastest flew from New York to London in less than three hours. When the British government established the Supersonic Transport Aircraft Committee in 1956 to explore the possibility of developing the world’s first passenger aircraft able to fly faster than the speed of sound, it could take as long as eighteen hours for a commercial jet to fly from London to New York. It was to take nearly twenty years for the committee’s work to culminate in the first commercial flight of a supersonic aircraft, but the subsequent performance of that jet, Concorde, exceeded even the most optimistic expectations. Routinely flying faster than twice the speed of sound, Concorde sported a take-off speed of 250 mph (400 kmph) and a cruising speed of 1,350 mph (2,160 kmph) at an altitude of up to 60,000 feet, twice the height of Mount Everest. At its fastest on 7 February 1996, Concorde flew from New York to London in just 2 hours, 52 minutes and 59 seconds, less than a sixth of the time that the same journey would have taken by air in 1956. Hailed for its beauty as well as its speed, Concorde seemed to belong less to the modern world than to the future. During 27 years of commercial service from 1976 to 2003, it became one of the best-loved engineering design projects of the 20th century. An exemplar of technological excellence, Concorde struck such a strong emotional chord with the public that children cheered whenever they spotted it in the sky. Concorde was Britain and France’s response to the space race in which the US and the Soviet Union had battled for supremacy throughout the late 1950s and 1960s. Aircraft production had flourished during World War II, and in the late 1940s and 1950s many of the technologies developed for military use were adapted to make passenger aircraft faster and more powerful. The next logical step was to develop a supersonic passenger aircraft capable of flying faster than the speed of sound. The British government formed the Supersonic Transport Aircraft Committee in 1956 and the Bristol Aeroplane Company started work on the development of the Type 233 supersonic jet. The French were pursuing the same goal with Sud Aviation’s Super-Caravelle and, in 1962, the two countries decided to collaborate in the interests of efficiency and economy. The agreement was formalised as a treaty between the British and French governments, rather than a commercial contract. By this time both the Bristol Aeroplane Company and Sud Aviation had merged with other companies to become the British Aircraft Corporation and Aerospatiale respectively. The name Concorde was first used by President De Gaulle in 1963, and the British initially spelt it without an ‘e’. In 1967 Tony Benn, the minister for technology, announced that Britain would adopt the French spelling and squashed nationalistic protests by proclaiming that the ‘e’ stood for “excellence, England, Europe and entente (cordiale)”. When an irate Scot wrote an angry letter demanding to know what ‘e’ represented to his country, Benn replied that it was ‘Ecosse’, the French word for Scotland. The technical challenges facing the British engineers at Filton, Gloucestershire and their French peers in Toulouse were immense, as were the political and economic problems that dogged the project from the start. When the collaboration began in 1962 Concorde was expected to cost between £150 and £170 million. The first prototype was scheduled to fly in late 1966 and the Certificate of Airworthiness to be issued at the end of 1969. France was to complete 60% of the work on the airframe and 40% of the engine, and Britain 40% of the airframe and 60% of the engine. In reality the project was so complex that it took much longer and cost far more. The radical implications of Concorde’s extraordinary speed for its weight, shape, noise and components meant that every element of its design was dramatically different from that of a conventional jet, as were the safety requirements. An early design decision was that its wings should be a slender, swept-back triangular shape, rather than rectangular like a Boeing 747’s, to allow Concorde to move easily through the air at exceptionally high speed. These triangular or ‘delta’ wings not only optimised speed by reducing drag, but provided sufficient lift for take-off and landing at subsonic speed, and enough stability during flight to eradicate the need to install horizontal stabilisers on the tail. The shape of the wings had important implications for the design of one of Concorde’s most famous features – its long needle-shaped nose. A delta-winged aircraft has to take off and land at steeper angles than one with rectangular wings, and Concorde’s pilots would have been unable to see the runway if its nose had been conventional in shape. To resolve this and to maximise aerodynamic efficiency, Concorde’s nose was designed to tilt by 13 degrees. During flight the nose was raised, and when Concorde landed it was lowered to give the pilots an unobstructed view of the runway. The problem of the noise emitted by the powerful engines developed for Concorde by Rolls-Royce in Britain and SNECMA in France proved less tractable. It was a struggle from the start to secure approval for Concorde to be permitted to fly to and from New York, and the noise issue meant that the number of airports where it was authorised to operate remained restricted. Similarly, Concorde’s development was marked by the struggle to squeeze in as many seats and as much cargo as possible, to optimise its potential for income generation, while minimising its size and weight. Made mostly from aluminium, the resulting aircraft was 203 feet 9 inches (62.1 metres) long, 37 feet 1 inch (11.3 metres) high with a wingspan of 83 feet 8 inches (25.5 metres). Concorde stretched between 6 and 10 inches during flight as the airframe heated – with the cabin becoming perceptibly warmer – even though it was coated in a white paint specially developed to dissipate the heat. In an era when luxury was still equated with the grandeur of size, one of the most surprising elements to Concorde passengers was to discover that the cabin was so small, as were the seats. The cabin was only 1.8 metres high with space for just 100 seats – 40 in the front section and 60 in the rear – with no space for overhead storage, which meant that cabin baggage was tightly restricted. Each seat on Concorde was considerably narrower than its equivalent in the first and business class cabins of British Airways and Air France. As Concorde only flew during the day, its compact seats did not cause too much discomfort as passengers did not sleep on them overnight. Each of the four Rolls-Royce/SNECMA Olympus 593 engines produced 38,000 pounds of thrust. The most powerful pure jet engines in commercial flight, they used reheat technology to add fuel to the final stage of the journey, thereby providing extra power for take-off and for the transition to supersonic flight. Part of the fun for Concorde passengers was hearing the pilot’s description of its progress during the flight as it gathered speed and gained height, eventually cruising at Mach 2, 1,350 mph or 2,160 kmph, twice the speed of sound, as high as 60,000 feet or twice the height of Mount Everest. Each Concorde had a range of 4,143 miles (6,667 km) and the capacity to carry 26,286 gallons (119,500 litres) of fuel. Typically it consumed some 5,638 gallons (25,629 litres) of fuel during each hour of flight. On 2 March 1969, Concorde 001 set off on its first test flight from Toulouse and the first supersonic flight was completed on 1 October that year. It then took another six years to secure the Certificate of Airworthiness. The testing of Concorde was unprecedented and is still unsurpassed today. The prototype, pre-production and first production aircraft undertook 5,335 flight hours, some 2,000 of which were supersonic. As a result Concorde was submitted to four times as many tests as standard commercial aircraft. The delays and political problems – from successive changes of British governments, to the sustained disapproval of Britain’s principal ally, the US – contributed to an escalation of the development budget, which is believed to have reached to £1 billion by 1976, when Concorde finally began commercial flights. At the start of the Anglo-French collaboration, airlines from over a dozen countries had expressed interest in ordering Concorde, but by the end of its development only two remained, British Airways and Air France. Bookings opened for the first commercial supersonic flights on 14 October 1975. The British Airways Concorde flew from London to Bahrain on 21 January 1976 and the Air France Concorde from Paris from Rio de Janeiro. As flights to New York were banned because of noise concerns, British Airways and Air France began Concorde’s US flights to Washington, but by late 1977 New York had succumbed by allowing Concorde to fly there. A total of 20 Concordes were constructed: six for development and 14 for commercial service. More than 2.5 million passengers flew supersonically on the British Airways Concorde alone between 1976 and 2003. A typical flight from London to New York was three hours and 20 minutes, compared with seven hours for a Boeing 747 jumbo jet. As Concorde flew twice as high as conventional long haul jets, turbulence was rare and passengers could see the curvature of the earth through the windows. Nicknamed ‘Big Bird’, Concorde was cherished as a national design treasure in both Britain and France, and was soon used for celebratory flypasts on special occasions. Concorde held the distinction of being the world’s safest working passenger aircraft until 25 July 2000 when Air France Flight 4590 crashed in France killing 113 people including all of the passengers and flight crew. Air France suspended Concorde flights, as did British Airways. After an overhaul British Airways resumed flights on 11 September 2001. On the same day, the World Trade Center in New York was destroyed by terrorists. International travel declined steeply and the relaunched Concorde struggled financially. Another problem was that, as no supersonic competitors had emerged, there had been no pressure to upgrade Concorde or to invest in new suppliers and sub-contractors. As a result, maintenance costs had risen steadily and keeping Concorde in flight was increasingly expensive. On 10 April 2003, British Airways and Air France announced that they were withdrawing Concorde from service by the end of the year. On 24 October 2003 Concorde completed its final supersonic flight as the world’s fastest passenger aircraft. BIOGRAPHY 1956 Formation of Britain’s Supersonic Transport Aircraft Committee. 1962 Britain and France agree to collaborate on the development of a supersonic aircraft through British Aerospace Company and Aerospatiale respectively, with Rolls-Royce and SNECMA developing the engine. 1963 President Charles De Gaulle of France introduces the name Concorde. 1965 Launch of pre-production designs. 1966 Assembly of the Concorde 001 and 002 prototypes begins. 1969 First test flights of Concorde 001 and 002, and the first supersonic flight. 1975 British Airways and Air France accept bookings for Concorde’s first commercial flights. 1976 On 21 January Concorde begins commercial flights from London to Bahrain and Paris to Rio de Janeiro. 1996 Concorde flies from New York to London in the record time of 2 hours, 52 minutes and 59 seconds on 7 February. 1999 Two British Airways Concordes fly in supersonic formation to chase a double eclipse of the sun. 2000 A total of 113 people are killed when an Air France Concorde crashes in France. Air France suspends Concorde flights, followed by British Airways. 2001 Concorde resumes commercial service, but faces financial problems after the decline in international travel following the 11 September terrorist attacks in New York. 2003 British Airways and Air France announce Concorde’s retirement. Concorde completes its final flight on 24 October. FURTHER READING Brian Trubshaw, Concorde: The Complete Inside Story, Sutton Publishing, 2005 Peter R. March, The Concorde Story, Sutton Publishing, 2005 Kev Darling, Concorde, The Crowood Press, 2004 Brian Calvert, Flying Concorde: The Full Story, The Crowood Press, 2002 Gunter Endres, Concorde: Aerospatiale/British Aerospace Concorde and the History of Supersonic Transport Aircraft, The Crowood Press, 2001 Wolfgang Tillmans, Concorde, Walther Konig, 1997 © Design Museum.designmuseum.org |

Damon Murray (left) and Stephen Sorrell (right) © Gordon Murray 2004

Damon Murray (left) and Stephen Sorrell (right) © Gordon Murray 2004

FUEL/GIRL 1991 Design + Production: FUEL

FUEL/GIRL 1991 Design + Production: FUEL

Diesel clothing catalogue, 1992 Design: FUEL Client: Diesel

Diesel clothing catalogue, 1992 Design: FUEL Client: Diesel

Virgin Records poster, 1992 Design: FUEL Client: Virgin Records

Virgin Records poster, 1992 Design: FUEL Client: Virgin Records

Pure Fuel, 1996 Design + Production: FUEL

Pure Fuel, 1996 Design + Production: FUEL

Fuel 3000, 2000 Design + Production: FUEL

Fuel 3000, 2000 Design + Production: FUEL

DAKS E1 press advertisement, 2001 Design: FUEL Client: DAKS Simpson

DAKS E1 press advertisement, 2001 Design: FUEL Client: DAKS Simpson

adidas press advertisement, 2001 Design: FUEL Client: adidas

adidas press advertisement, 2001 Design: FUEL Client: adidas

Tracey Emin exbhition poster, 2002 Design: FUEL Client: Modern Art Oxford

Tracey Emin exbhition poster, 2002 Design: FUEL Client: Modern Art Oxford

Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopaedia, 2004 Design + Production: FUEL

Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopaedia, 2004 Design + Production: FUEL

Cover for Let's Bottle Bohemia, The Thrills, 2004 Design: FUEL Client: Virgin Records

Cover for Let's Bottle Bohemia, The Thrills, 2004 Design: FUEL Client: Virgin Records

FUEL publishing promotion, 2005 Design + Production: FUEL

FUEL publishing promotion, 2005 Design + Production: FUEL

| Article 7. FUEL Graphic Designers Design Museum Collection Combining commissioned work – typically from fashion, music and art clients – with self-initiated projects, the British graphic designers Damon Murray and Stephen Sorrell have worked together as FUEL since 1991 from a studio in the Spitalfields area of London. From the staccato illustrations on a series of album and singles covers for The Thrills, to the glacially decadent portrait of the photographer Juergen Teller and actor Charlotte Rampling on the cover of his Louis XV/Ich bin Vierzig book, the work of the London-based graphic designers FUEL always has an arresting, even sinister quality. Founded in 1991 by three graphic design students at the Royal College of Art in London, FUEL was originally composed of Damon Murray and Stephen Sorrell, who has studied together at Central St Martin’s, and their friend Peter Miles. Their first joint project was the magazine Fuel, which they produced at the RCA, made the focus of their degree show and which elicited their first commercial commission from the Diesel fashion label. After graduation they opened a studio off Brick Lane in the Spitalfields area of London. Murray and Sorrell, both born in 1967 in London and Maidstone respectively, still work together as FUEL, but Miles left in 2004 when he moved to New York to work for the fashion designer Marc Jacobs. Over the years they have continued to publish Fuel magazine as well as other self-initiated projects, and have built up a loyal cadre of clients in art, fashion and music, including Juergen Teller and the artists Jake and Dinos Chapman and Tracey Emin. Print remains the focus of FUEL’s work, but they have also experimented with moving images, notably by creating the film titles for Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation. Q. You met at the Royal College of Art and began publishing the magazine Fuel. What drew you to self-publishing? A. We were bored with the set projects at college and so started a magazine. The content was image-based because good copy was hard to source. The pages were high impact – with bold images and headlines – often containing ambiguous or thought provoking messages. We didn’t really think of it as self-publishing – more as an outlet for our work. We felt we could achieve more as a group than as individuals. Q. Do you feel that your education – design or otherwise – influenced the way you work now? A. In terms of design education Central St Martins gave us space to develop freely while the RCA gave us something to work against as a group. We were quite driven at college to produce work fast and to make the most of our time there. We still work quite quickly. Q. What are your design influences? A. Various things influence the way we work. The value of influences is in discovering your own. A list of reference points isn’t a short cut to our thoughts or approach. Influences or things we like: vinyl records Barry Kitchener Polaroids Spike Milligan Bauhaus Tou r de France Peter Blake concrete Paul Auster Russia Raymond Chandler The Who Spitalfields Q. Fuel, the magazine, and various associated publications have been produced sporadically over the years. Without a client driving you on, what leads to each new issue or book? A. We have always had an urge to produce work that is self-generated and not confined to a client's brief. When we have ideas that cannot be used in a commercial context the publications give us the opportunity or reason to produce the work. Q. What were your earliest commercial jobs? How did they relate to your self-published work? A. While still at the RCA, some of our earliest commercial work was for Diesel clothing. They saw an article about our first magazine FUEL / GIRL in Creative Review magazine and commissioned us directly from that. We were given a free reign to come up with images involving their clothes for their catalogue, including setting them on fire and freezing them. We also produced a series of screen-printed posters for Virgin Records as an installation for its foyer. These posters were like large scale pages from our magazines, updated every six weeks. These commercial projects funded the printing of our magazine and helped set up our studio after graduating. Q. You have continued to initiate various publishing projects throughout your career – such as Wow Wow and Steidl Fuel. What prompts these projects, and how do they relate to the rest of your design output? A. The ideas are always driving these projects. They are based on ideas we’ve had or subjects we are interested in and want to develop. Q. In recent years you have produced a number of catalogues and books for artists. Is the artist/designer relationship very different to that with other clients? A. Often artists want good but quite simple design, they don’t require another voice. Like any client/designer relationship, it helps when you get to know them and can develop an understanding. Tracey Emin and Jake and Dinos Chapman live very near our studio so we have got to know them quite well. Working with them is quite sociable which makes it more enjoyable. Q. You have also worked for a number of fashion clients. Do fashion clients have demands that are very specific to their field? A. Fashion clients want ideas and good art direction more than anything else. With both artists and fashion clients the fine details are very important. Q. How would you characterise the perfect relationship between designer and client? A. Time to develop trust and understanding. Q. What would be your ideal job? A. A book or magazine for a major client where we have the freedom to generate the content. Q. What is your favourite piece of your own work? A. The Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopaedia is a book we are happy with. The drawings and photographs are quite extreme and unlike anything we had seen before. In contrast the packaging of the book is quite inviting. It was also a commercial success. Q. You have been working together since 1991. How has your studio evolved over that time and what are your plans for the future? A. Our work has developed over the years but the approach to work is fairly consistent. Peter Miles left Fuel in 2004 to live and work in New York so that created a change. However, our studio set up in Spitalfields has not really changed that much in more thirteen years – it’s a floor in a Georgian house with a big table and a couple of Macs. We are now publishing books ourselves as well as designing and editing the content, an exciting development for FUEL. For more information on British design and architecture go to Design in Britain, the online archive run as a collaboration between the Design Museum and British Council, at www.designmuseum.org/designinbritain Visit FUEL’s website at fuel-design.com © Design Museum |

Íå íàøëè, ÷òî èñêàëè? Âîñïîëüçóéòåñü ïîèñêîì: